on the normativity of excitement and the possibility of aesthetic appreciation

or, what we're doing when we disagree about the boring and the beautiful

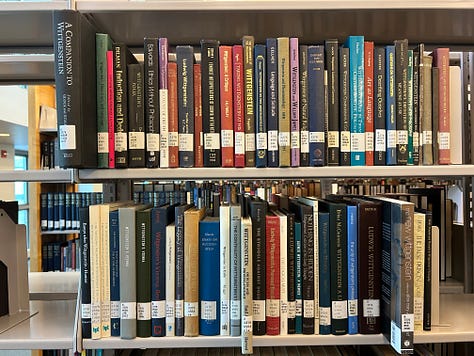

earlier this summer i returned to my alma mater for the first time in ten years. i only had about an hour there, so naturally i went to the library. among my slowly receding stock of steamy college memories, few stand out like my first encounters with transcendental arguments.

on fall mornings early in the term, when had time for research outside my actual coursework, i’d grab a couple books from the library and hunker down at the bakery in town for a few hours of underlining, page flipping, and dog-earing. almost all of it was wittgenstein, wittgenstein commentary, or wittgenstein-influenced contemporary an analytic philosophy.

the subject was usually skepticism, in all its flavors, not just skepticism about perceptual experience. following the lead of philosophers like john mcdowell and james conant, i became convinced that transcendental arguments could be adapted to all these skepticisms — including skepticism about the meaning of words, aesthetic judgements, and value.

i also began thinking that transcendental arguments could bind together other philosophical views to which i was becoming attracted — like fitting attitude theories of value, knowledge-first epistemology, disjunctivism, and metaphilosophical quietism. turning these ideas over together felt almost visceral. it was the kind of intellectual relief wittgenstein described as “shooing the fly out of the bottle.”

transcendental argument is a technical term for an argument that responds to skepticism about claims in some area by focusing on how we could so much as disagree about those claims in the first place. transcendental arguments begin from the fact that for the skeptic to be able to lure us into her argument, she and her audience need to understand what one another are talking about in the first place. if they did not, their vocalizations could not be recognized as an argument, or even conversation, at all.

transcendental arguments then attempt to establish that for this disagreement between the skeptic and her interlocutor to be possible, we need to know what would count as getting things right in that area of discourse over which the skeptic wants to cast doubt.

if this attempt is successful, the rhetorical effect of a transcendental argument is to shift the burden of proof back to the skeptic now who has to give some alternate account of how she and her interlocutors could have found themselves in disagreement at all. she owes this account because she also wants to conclude that we can’t ever know what it would be to get things right in those areas, and the transcendental argument has asserted that this is incompatible with understanding each other’s judgements in that area.

in other words, the skeptic has to give us some kind of story about how she and her interlocutors could understand each other to be talking about the same things (say, aesthetics, or perception, or the meaning of words and signs) without appealing to the idea that we sometimes know what it would be to get things right in our judgments about those things.

the canonical example is skepticism about perceptual judgments. the skeptic about visual perceptual usually begins her argument by claiming that things could appear to us just as they do now if we were having a sophisticated and long-lasting hallucination. the cause of the hallucination could be a sophisticated orchestration of neural inputs managed by a mad scientist who has our brains kept in a vat to carry out this experiment, matrix-style. if we were such a brain-in-a-vat, the skeptic continues, there would be no way of knowing; everything in our visual environment might have been caused by this supposed mad scientist. and so, the skeptic concludes, there’s no way to know if things we visually perceive really are out there around us, or just hallucinations “in” our minds. there’s no way of knowing if our judgments about visual perception are true — unless they are merely judgments about how things appear to us.

that should all sounds familiar.

transcendental arguments address this skeptic by questioning her entitlement to the claims with which she began. it calls attention to the skeptic’s claim that things in our visual perception appear to us a certain way, and asks what could give the skeptic the idea that this is even possible if her skeptical conclusion is also true? why would we even have the idea of objects being “out there” in a perceptible environment if it weren’t the case that we were sometimes right about this?

if what the skeptic says is true though, it becomes fairly mysterious what it would be to be right in our perceptual judgments. while the proponent of the transcendental argument has an easy story for what could give us the idea of things merely appearing to be thus and so (we have this idea because we know what it would be for them to actually be thus and so), the skeptic does not. in our everyday life, untroubled by skepticism, we know what it would be to be for our perceptual judgments to succeed, and that’s how we make sense of what it would be for them to fail.

the skeptic may try to say that the mad scientist implanted the requisite ideas, but the transcendental response is to just globalize the burden-shifting challenge to all the agents in the skeptic’s scenario. what would give the the mad scientist the idea of such a distinction? surely the skeptic’s gambit could apply to them just as well. the skeptic might try to imagine a second mad scientist — evil deceivers all the way down. but that wouldn’t dislodge the transcendental argument’s challenge: that for us to be entitled to the idea of things even appearing thus and so, we have to also know what it would be to get things right in our judgement that things are in fact thus. knowledge, as contemporary philosopher and mega-dork timothy williamson would say, is conceptually, metaphysically, and developmentally prior to mere belief. we can’t make sense of things being the other way around.

there are other consequences of this view — if knowledge must come first in a theory of visual perception for us to make sense of the idea that things could even appear to us anyway at all, then we can’t give a theory of perception which treats perception and indistinguishable hallucinations as fundamentally the same kind of thing, save for some extra conditions which distinguish the successful perceptions from the hallucinations. the latter is actually the standard theory of visual perception — founded on the idea that because the visual sciences tell us that perception and indistinguishable hallucination are the same kind of neurological process, then a theory of perception must also treat them as the same kind of metaphysical phenomenon. perceptions are “representations” of the world just as are hallucinations. except in the case of perception, there are actually objects in the world that causes the representation, rather than electrical impulses from a mad scientist directly to our brains.

opposed to this metaphysical view about the nature of perception is the view philosophers call disjunctivism about perception: while the sciences may correctly tell us that the causal processes enabling perception and hallucination are the same, this does not license the inference that perception and hallucination are therefore the same kind of thing, save for some extra causal luck in the perceptual cases. in a theory of perception, successful exercises of a perceptual capacity are different in kind, and conceptually prior to, unsuccessful exercises (hallucinations) even if the causal processes enabling these things are the same. we can’t analyze perception without understanding it as essentially involving knowledge about things in our perceptual environment.

an interesting feature of transcendental arguments is that they do not so much as refute the skeptic by claiming what she says is false. instead, they should be viewed as a rhetorical, burden-shifting challenge — one that insists the skeptic has not done enough to entitle herself to her premises. absent that entitlement, the proponent of the transcendental argument insists we can safely ignore the skeptical challenge. the result is a kind of metaphilosophical quietism — transcendental arguments do not teach us something new about our justification for perceptual beliefs, or the nature of perception. rather, they provide a sophisticated defense of the naive, common sense views that perception is a relation to objects; a capacity for knowledge about them.

these may sound like sophisticated philsophical claims, but that’s mostly because my writing is shit and i can’t shake the jargon. at the end of the day, transcendental arguments are supposed to just leaves us where we started before the interruption of skepticism. metaphilosophical quietism is the view that philosophy actually has nothing new to teach us about our relation to the world and ourselves. instead, substantive philosophical views that would purport to do as much are actually rooted in confusions that — once removed — leave only common sense. unlike a science that adds to our knowledge of the world, philosophy is more like medicine: a discipline for which there would be no need in a perfect world where no one ever got sick.

…

that’s how transcendental arguments stitch these four views together: knowledge comes first, perceptions are different in kind than hallucinations even if they are not knowably distinct, and philosophy leaves everything as it is; dispelling confusions rather than adding substantive knowledge.

so too with evaluative attitudes like boredom. our discourse about the boring and the beautiful are similar to our perceptual thought and talk. in order to disagree about what is boring or beautiful, we must know what it would be to get things right in our judgments of these things. i’ll argue that while we must acknowledge the objectivity of the boring and the beautiful, it would be a mistake to think we could only do so via criteria about what makes something boring or beautiful. instead, these subjects are better understood in terms of a non-reductive, fitting attitude view.

fitting attitude theories of value explain the truth of our evaluative judgements in terms of the fit between the objects that merit that attitude and the attitude itself. what is it for something to be funny? for it to merit amusement. what is it for something to merit amusement? for it to be funny. this blatant circularity is not vicious, because fitting attitude views tell us something important about the relationship between our evaluative attitudes and their objects. namely — that neither is analytically prior to the other.

what is it for something to be boring? to merit boredom. which things merit boredom? the boring things, naturally. what is it for something to be beautiful? same story — to merit aesthetic appreciation.

if discourse about the boring and beautiful were totally mysterious to us, this explanation wouldn’t be much help. but it is helpful if we want to find a way to make sense of what we’re doing when we disagree about the boring and the beautiful. we’re engaged in a truth-seeking activity, where the possibility of our getting things wrong depends on our ability to get them right.

aesthetic appreciation and boredom are different from vanilla perceptual judgements because we want to recognize a lot of systematic and unproblematic variance in our judgements about these things that are sometimes not best understood as disagreements. what is fun for a kid is often not fun for an adult; what is aesthetically engaging for some groups may systematically diverge from others. in many contexts, disagreements between these parties would be strange — best not understood as disagreement at all, or if it is, merely a kind of “pretend” disagreement. imagine the parent playfully arguing with their kid about whether digging holes in the ground is fun. it would take an elaborate set up to interpret this disagreement as full-throated.

that’s not a problem for a fitting attitude view of the beautiful and the boring though. because in practice even though the margins of unproblematic disagreement may be wider here than in perceptual cases, the margin of agreement is wider still. to paraphrase the philosopher donald davidson: the possibility of our disagreement depends upon on a vast background of agreement. to recognize ourselves as talking about the same thing requires as much.

…

a few objections to this haphazard ensemble of views may have occurred by now. first, what about discourse around fictional, or controversial concepts? surely we understand what we’re talking about when we talk about witches or ether; does a transcendental argument mistakenly conclude that these things must exist if we can understand ourselves as disagreeing about our knowledge of them?

it does not. transcendental arguments don’t conclude that anything must exist. they assert that for our discourse about a subject to be understood, we have to know what it would be for some of our judgements about it to be true. for witches and ether this is pretty straightforward. just imagine the world in which something with their properties actually exists. that’s what it would be for it to be true. religious judgments are a little trickier. people initiated into religious language do often appear to agree in their judgments — about say, what is sacred and profane. but if we don’t know what it would be for some religious judgments to be true, that may just mean we have to regard them as nonsense until we grasp their meaning. wittgenstein seemed to think as much.

a more sophisticated objection to transcendental arguments was made by my late grad school professor barry stroud. stroud argued that the best a transcendental argument can do against the skeptic is to establish that for things to appear a certain way, we must believe that some of our judgements about these things can be right — not that some of these judgments must actually be right. the transcendental argument cannot cross a “bridge of metaphysical necessity” from beliefs to reality.

i never convinced professor stroud that this objection misconstrues transcendental arguments and then begs the question against them. but that is still what i maintain. for any of our beliefs about perception to make sense, we have to know what it would be for some of them to be right. if the skeptic wants to claim that this isn’t true, she' owe us some explanation of why and how our beliefs about the world could appear to be world-directed in the first place. what would give us the idea? this is easy for the purveyor of a transcendental argument. knowledge is primitive. it is analytically, metaphysically, and developmentally prior to belief. while stroud’s “bridge” analogy treats our beliefs as metaphysically unproblematic, as simply given, the transcendental argument shifts the rhetorical burden by insisting that it’s mysterious how this could be. something has to make it possible for us to have them, and we need a story of how they could possibly be about something in the first place. what would so much as give us the idea that these beliefs aim at something, that they have an object?

the last objection you might have is that all this technical talk seems pretty non-trivial for a set of views which are supposed to bring us back to simple common sense. in what world do transcendental arguments, disjunctivism, knowledge-first epistemology, and fitting attitude theories of value as add nothing new to our stock of knowledge about the world?

first off, yes, i’m sympathetic to this objection. in my less doubtful moments though, i think of these views like immunizations. they are not like the discoveries made by science. they are not things we learn. they are tools for unlearning certain things we took to be true but were actually philosophy-induced confusions — illnesses. these views are palliative for such confusions, but only useful for people in the grip of bad philosophy. for those blessed enough to be untroubled, they offer nothing.

there may be few who are actually untroubled though. half-hearted skepticism rooted in half-baked relativism seem to be fairly common in my experience. equally common is a desire to stave off those outcomes via generalized principles and reductive theory that will help us settle evaluative disputes in advance.

these temptations are both unhealthy. against them, sophisticated philosophy can steer us back to earnest and unproblematic disagreement which cuts between the scylla of skepticism and the charybdis of dispute-settling theory. evaluative life is hard and messy, but it is also real and truth-guided. the only way to deal with that is to get better at it. just don’t expect any help from philosophy.